A&F Auto Parts, operational in Indiana from 1984 to 1989, serves as a compelling case study for small business owners navigating the auto parts industry. Founded with the vision of meeting local auto parts demands in Brownsburg, Indiana, the firm’s story illuminates both the potential and challenges small businesses face. Through its history, economic contributions, technological evolution, societal role, and ultimate dissolution, we uncover valuable insights into sustaining a small business in competitive markets. Each chapter delves into various aspects of A&F’s journey, providing a holistic view that reveals lessons that can aid current entrepreneurs in their quest for success.

Founding, Flux, and the Fate of a Local Auto Parts Outfit: The A&F Auto Parts Story

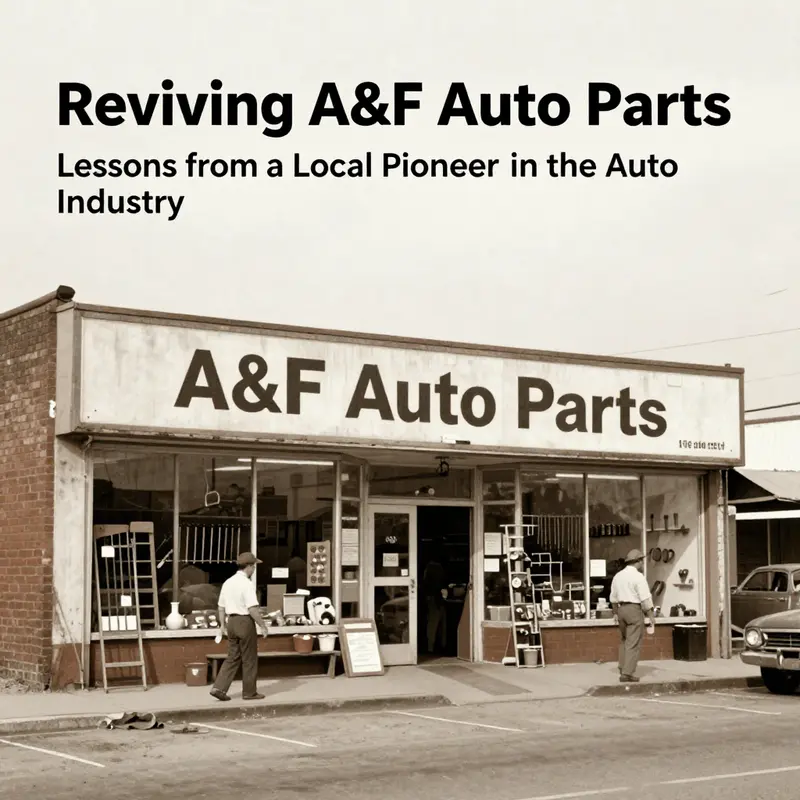

A&F Auto Parts Inc. sits in the margins of memory and records, a small waypoint in the wider map of the Midwest’s automotive aftermarket. Its pages are modest: a company incorporated in Indiana on April 19, 1984, a private for-profit entity anchored at a street address that local business lore still remembers as a place where parts and conversations circulated with the rhythm of a neighborhood shop. The registration details—Corporation Number 198404-603, the principal address at 1044 E Main St, Brownsburg, IN 46112, and the named agent, Albert Dieren, whose own address was 906 E Main St—mark a precise moment when a local entrepreneur and his partners chose to enter the market as suppliers of mechanical components and consumables in a region whose auto culture ran along midwestern arteries of commuting and trucking alike. These neat lines on a public record mask the larger human story that often never appears in sales catalogs or cataloged inventories: a small business trying to make its way in a field defined by constant motion, shifting demand, and the stubborn realities of local economies.

To read A&F Auto Parts through that lens is to understand the nature of an aftermarket landscape that in the 1980s was both buoyant with opportunity and unforgiving in its competition. The era’s vehicles demanded a steady supply of parts, and regional shops could thrive when they built trust with nearby garages, beacons for do-it-yourselfers, and intermediaries who understood the timing of a repair more than the price of a single bolt. Brownsburg, a town that functioned as a node in a broader network of Indiana communities, provided a receptive base for a business that needed reliable access to stock, a door that opened onto a steady stream of customers, and a name that signified continuity in a market where inventories fluctuated with the seasons, the recalls of parts catalogs, and the vagaries of supplier relationships. In this setting, the A&F name would become, for a handful of years, a practical reference point for those who needed to fix, restore, or upgrade a vehicle rather than to chase new car trends or the era’s high-profile retail brands.

The lifecycle of A&F Auto Parts is instructive precisely because it is not a chronicle of meteoric growth or of a spectacular exit. It is a compact narrative about a five-year window in which a local venture existed, tried to scale, and ultimately dissolved. Public records show that the company ceased operations and was formally dissolved on October 30, 1989. The brevity of the life—just five years from inception to dissolution—does not diminish its relevance. Instead, it underscores a recurring dynamic within the auto parts sector: many small, locally anchored enterprises come into being during periods of consumer demand and then recede as market conditions, financing, or leadership priorities shift. The dissolution filing, a sober administrative action, signals a legal and organizational wind-down rather than a dramatic retail reversal. It marks the end of a formal corporate identity, even as the physical landscape of Brownsburg and the surrounding region continued to pulse with vehicles of all kinds, old and new, on roads that were constantly being repaved or repurposed.

What remains legible in the archival footprint of A&F Auto Parts is the interplay between local governance and business life. The agent’s role in the incorporation—Albert Dieren stepping in as the registered contact—speaks to a governance structure that relies on individuals who can bridge the private sphere of ownership and the public sphere of regulatory compliance. The principal address on E Main Street is a geographic anchor; it connects the enterprise to a tangible community. In the absence of publicly touted achievements or long lists of catalog numbers, what the records reveal is a portrait of a business that functioned within a tightly circumscribed climate: modest scale, local demand, and a lifecycle that could be measured in years rather than decades. The historical record thus becomes a lens through which we can study the tempo and texture of small-scale enterprise in a sector that often appears as a uniform, nationwide market to outsiders. It reminds us that the auto parts ecosystem—quotes, orders, parts identification, and the logistics of supply—depends on a web of local actors who contribute to a much larger chain of maintenance and repair.

Interpreting A&F Auto Parts within this framework invites a meditation on the broader challenges faced by small distributors in the aftermarket space. The 1980s in the American Midwest were a period of evolving consumer expectations, a shifting car fleet, and the emergence of new procurement channels. While larger regional players could leverage bundled purchasing, extended credit terms, and more visible branding, smaller shops had to rely on proximity, reputation, and the trust built with garages and DIY enthusiasts who preferred a quick, reliable sourcing path. The five-year arc of A&F can be read as a microcosm of the risk calculus that many similar ventures confronted: the need to balance cash flow with inventory turnover, the difficulty of maintaining a diverse enough catalog to meet varied repair needs, and the challenge of sustaining relationships with suppliers when demands moved in unpredictable cycles. In this sense, the dissolution of the entity is not merely a formal end; it is a data point about the volatility of local commerce and the fragility of a business model that may work well on paper but requires constant adaptation to survive in practice.

The narrative also invites reflection on what kinds of memory persist when a business dissolves. Public archives preserve the name, the address, and the legal steps, but they seldom capture the day-to-day rhythms—the conversations with customers, the rush of inventory shipments, the late hours spent aligning orders with the needs of a busy repair shop across town. Yet those implicit memories matter to anyone who studies how local economies function, how job opportunities are created or not created, and how entrepreneurial energy in a small town like Brownsburg feeds into a much larger nationwide economy of parts and vehicles. The A&F Auto Parts record is a reminder that every local venture is a node in a sprawling network; its existence, even if short, contributed to the ongoing supply chain that kept cars on the road and families on the move. It also raises questions about what sustainability looks like in a sector where product life cycles are tied to consumer trends, vehicle vintages, and the pace of technological change in the broader automotive world.

From a methodological perspective, reconstructing a company’s lifecycle from limited public records challenges historians and analysts to combine formal documents with contextual knowledge. The dates, addresses, and agent details provide a scaffold, but the deeper texture comes from understanding the regional economy, the nature of retail and wholesale markets for auto parts, and the social fabric of the era. In the end, the A&F case highlights how local entrepreneurs navigated a field shaped by constant supply and demand, how small firms contributed to the resilience of the neighborhood’s automotive ecosystem, and how, when the final dissolution occurred, it left a trace that researchers could still follow years later. The record, though quiet, speaks in a quiet way about competition, risk, and the choices that define business life in a community context.

Looking ahead in this chapter series, A&F Auto Parts serves as a point of reference for readers who want to connect the micro-level trajectory of a single shop with macro-level themes in the auto parts industry: the alignment of inventory strategy with repair demand, the importance of local relationships for aftermarket success, and the inevitability that many ventures will be remembered not for grand expansion but for the steady, reliable service they offered in a hometown setting. The Indiana register, the dissolution date, and the agent’s information are more than archival details; they are a narrative skeleton that invites us to imagine the other, unwritten chapters—the late-night phone calls about missing parts, the visits from repair technicians seeking a reliable source, and the quiet negotiation of credit terms that kept a small shop solvent during lean months. In this sense, the A&F story is not an anomaly but a common thread in a sector that thrives on local trust, timely deliveries, and the ability to respond with speed to the needs of vehicles and their owners.

As the chapter closes on the record of a business that once existed, the broader lesson remains: in the world of auto parts, small, locally anchored companies contribute to a continuous lifecycle that sustains vehicles and, by extension, the daily routines of communities. The durability of this contribution does not always show up as years of expansion; sometimes it appears as a bright, brief spark that lights up a town’s supply chain and then, like so many other small enterprises, fades into the quiet of a public archive. And in that quiet, the significance persists—the recognition that every local shop, no matter how short its run, participates in a larger economy that keeps moving forward, one part, one order, and one customer at a time.

External reference: https://www.qichacha.com/companydetail198404-603.html

Local Torque: How A&F Auto Parts Shaped Indiana’s Auto Parts Ecosystem

A&F Auto Parts operated as a small but meaningful node in Indiana’s dense automotive network. Though the company existed for a brief period in the 1980s, its activities reflect how local distributors underpin regional supply chains. Small parts businesses like A&F connect repair shops, independent technicians, fleet operators, and retail customers. They translate factory and aftermarket production into usable parts on the street. This chapter examines that role and draws out the broader economic implications for Indiana’s auto market.

A&F Auto Parts functioned within a state economy already oriented to vehicles. Indiana hosts manufacturing plants, tier suppliers, and distribution centers. Those large facilities anchor regional employment and capital investment. Local distributors supply the finishing link: timely parts, diagnostics, and knowledge. When a small company like A&F stocked brake pads, bearings, filters, or electrical components, it enabled repair shops to turn vehicles more quickly. Faster turnaround means lower downtime for businesses and individuals. This velocity translates into measurable value across the local economy.

The immediate economic contribution of a local parts shop is straightforward. It hires staff, purchases inventory, and pays property costs and taxes. Each wage dollar spent becomes local consumption and supports other businesses. Each supplier purchase potentially supports regional wholesalers, transporters, and packaging services. These transactions produce multiplier effects that extend the original expenditure. For instance, a parts shop’s payroll supports grocery stores, housing, and local services. The shop’s inventory purchases support distribution jobs that may not be visible in retail tallies but matter for community employment.

Beyond direct spending, local distributors also provide an essential service that has broader productivity effects. Independent repair shops and fleet operators depend on local parts for reliability. Without nearby suppliers, shops face longer wait times and higher inventory costs. Those costs can reduce competitive margins and raise consumer prices. By offering parts locally, companies like A&F helped keep maintenance costs lower for vehicles. That reduction in costs supports businesses that rely on vehicle fleets and saves household budgets. These savings aggregate across thousands of vehicles and thousands of repair events each year.

Small parts providers are also knowledge hubs. Staff often possess tacit, experience-based knowledge about fit, compatibility, and repair best practices. That know-how shortens diagnostic times and reduces trial-and-error orders for shops. The value of that expertise is hard to capture in standard economic statistics, yet it is crucial. Knowledge transfer from local distributors to mechanics enhances service quality, extends component life, and supports innovation in repair techniques. In rural or smaller urban markets, this human capital can be the difference between a viable repair ecosystem and one that depends heavily on distant suppliers.

The presence of many small distributors contributes to supply chain resilience. Large manufacturers and national distributors provide scale, but localized businesses offer flexibility. They can pivot to different products, keep smaller inventories for less common parts, and react to immediate demands. During disruptions—strikes, transportation slowdowns, or sudden demand spikes—local suppliers reduce vulnerability by absorbing variation. This resilience matters for regional economic stability and for maintaining the mobility of workers who depend on cars to reach jobs.

Still, small operators face persistent challenges. Competitive pressure from national chains and online marketplaces compresses margins. Economies of scale favor larger distributors in purchasing and logistics. Regulatory and administrative burdens add fixed costs that are heavier for small firms. In A&F’s case, the company formed in the mid-1980s and dissolved within five years. While the specific reasons for its closure are not publicly documented in the sources available, the lifecycle of a small parts business commonly reflects these pressures. Market consolidation, capital constraints, or changes in local demand can all contribute to dissolution.

The loss of a local parts provider has localized economic impacts. Jobs disappear, procurement relationships break, and the knowledge network thins. Repair shops may face longer lead times and higher ordering costs. In aggregate, multiple closures can shift demand toward centralized providers, increasing dependence on longer supply chains. That concentration can make the regional market less resilient to shocks and reduce competitive options for consumers. Conversely, new entrants or surviving small firms sometimes fill the void, often adapting business models to include online ordering, broader product ranges, or mobile services.

A&F’s case also highlights the importance of place-based entrepreneurship. Small parts firms often start with owner-operators embedded in their communities. They leverage local reputations, existing relationships with mechanics, and a hands-on understanding of vehicle needs in their area. These characteristics support rapid market entry but can limit scalability. Access to capital and strategic partnerships can change that trajectory. When local entrepreneurs receive targeted support—through small business lending, workforce development, or supplier aggregation—their chances of long-term viability improve. Policy that recognizes this dynamic can amplify the contributions of dozens of similar firms across the state.

Measured against Indiana’s larger automotive footprint, a single local distributor’s monetary impact may appear modest. Yet the regional economy is built from such modest contributions. The auto sector’s large share of manufacturing value-added in the state depends on a layered ecosystem. Local suppliers facilitate the maintenance and operation of fleets, support aftermarket demand, and provide nimble services that global players cannot replicate cheaply. This layered structure enables the state’s broader sector to sustain output and employment even as technologies and market preferences evolve.

Understanding the true economic impact of a small firm requires better metrics. Traditional measures capture employment and sales. They often miss service speed, local knowledge, and the indirect benefits to other firms. To quantify these effects, researchers should track repair turnaround times, fleet downtime costs, and the substitution effects when a local supplier exits. Surveys of repair shops can reveal how often they rely on same-day parts and how closures alter their operations. Local tax filings or chamber of commerce records could provide historical revenue snapshots for defunct entities like A&F. Collecting these data would enrich the narrative of how micro-level actors shape macro outcomes.

There are practical lessons from A&F’s arc. First, diversification matters. Suppliers that combine retail, wholesale, and service offerings spread revenue risk. Second, specialization can be a strength when paired with deep local knowledge. A firm that becomes indispensable to a niche cluster of repair shops gains pricing power and customer loyalty. Third, modernizing procurement and inventory systems extends competitiveness. Even small shops can benefit from networked ordering platforms, inventory forecasting tools, and logistics partnerships that reduce carrying costs.

Finally, the regional policy environment influences the survival of local parts firms. Programs that ease access to credit, subsidize workforce training, or support technological adoption can bolster small operators. Equally, transportation infrastructure investments lower distribution costs for all suppliers. Local planning that preserves affordable commercial space helps too, because rising rents can displace thin-margin businesses. Recognizing the systemic role of small parts distributors can shape interventions that protect both employment and supply chain health.

A&F Auto Parts’ footprint in Brownsburg was finite, but its existence exemplifies the wider dynamics in Indiana’s auto parts economy. Local distributors knit together manufacturing, repair, and consumption. They create jobs, reduce operational friction for fleets, and add resilience to supply chains. Where small firms vanish, communities feel the change in subtle ways—longer repair times, altered procurement patterns, and lost local expertise. Strengthening this layer of the ecosystem requires attention to capital, technology, and policy design tailored to small operators.

For those studying regional automotive ecosystems, small distributors are critical subjects. They provide the operational glue that keeps vehicles moving. Future research that combines firm-level histories with region-wide supply chain analysis would better reveal the cumulative economic impact of shops like A&F. Meanwhile, local planners and industry partners can support resilience by nurturing the conditions in which independent suppliers thrive. Examples of aftermarket listings and inventory strategies can illustrate what small firms offer to local markets; see an example aftermarket listing for rims as a reference: 17-inch aftermarket rims listing.

For broader context on the industry trends that shape local markets, consult the detailed analysis at the following external resource: https://www.tdeconomics.com/research/automotive/north-american-auto-outlook-2025

null

null

Shadows on the Main: How A&F Auto Parts Reflected a Local Auto-Parts Ecosystem

The story of A&F Auto Parts, as it flickers through the archival record, is more than a date on a ledger or a name on a street corner. It is a window into a familiar, often overlooked layer of the automotive world: the small, locally rooted shops that kept daily mobility possible for everyday people. In Brownsburg, Indiana, a town on the fringe of a growing region around Indianapolis, a modest storefront at 1044 E Main Street once offered parts, advice, and a sense of continuity for drivers who relied on keeping their vehicles roadworthy. The official documents capture a five-year life span from its registration in 1984 to its dissolution in late 1989. They name the registered agent, Albert Dieren, and a precise street address, a reminder that small businesses live in place as much as in numbers. Yet the archival footprint stops short of narrating the lived experience of the shop, its customers, its staff, and its neighbors. What remains, then, is an opportunity to read between the lines and consider how such a business sits within the social and economic fabric of a community it touches, however briefly.

To understand the potential role of A&F Auto Parts in its community, one must start from the premise that auto parts stores, especially those anchored in small towns, perform more than the simple function of stocking items. They act as gateways to mobility, enabling families to repair and maintain their vehicles, preserving routines that hinge on reliable transport. In many towns, a local parts supplier is a node in a broader network that includes repair shops, independent mechanics, eager apprentices, and even neighbors who share a quick tip about a stubborn squeak or a stubborn rust spot. In these settings, the shop becomes a venue for tacit knowledge exchange—lessons learned from years of working with a particular community’s cars, climate-adapted needs, and the quirks of local driving patterns. While the historical record for A&F does not document explicit acts of community service or outreach, the position of such a shop within Brownsburg’s Main Street economy would likely have made it a familiar point of reference for people troubleshooting their daily transportation.

The 1980s, the decade during which A&F was active, were a period of transition in the auto parts landscape. National chains expanded their footprints, catalogs proliferated, and logistics networks began to emphasize efficiency and reliability. Small, independent stores found themselves navigating a market that favored scale and speed, yet many continued to thrive by leaning into local knowledge, personal service, and the ability to source hard-to-find components through regional distributors. In this context, A&F would have faced the pressure of larger, more resource-rich competitors while simultaneously benefiting from the loyalty of a clientele that valued proximity and trust. The interplay between competition and community loyalty often shaped the survival calculus for neighborhood shops. A&F’s five years, though modest in the grand arc of corporate life, is a reminder that a local shop can be briefly vibrant and nonetheless vulnerable to the shifting currents of a retail ecosystem that prizes breadth and speed.

What can be read from the available data is that the dissolution of A&F Auto Parts was final rather than incremental. The records mark a definitive end to its commercial status, a moment when the storefront would stop functioning as a parts hub and the street would move on without it. Yet the absence of a documented community initiative or partnership does not imply a lack of social presence. Small auto parts stores frequently served as informal support hubs: they offered guidance on maintenance tasks, pointed customers toward reliable repair options, and created a social space where locals could exchange news and practical knowledge. When such a shop closes, a particular kind of local memory fades. The loss is not just a product gap in a catalog; it is a rupture in the everyday flow of information, the subtle assurance that an approachable source exists for the questions that arise at the curb when a vehicle refuses to start or a radiator needs attention after a long winter.

The lifecycle of a small, independent auto parts business is often a stark reflection of the broader economy. Five years in operation suggests a period of initial establishment, some growth, and then a point at which sustained profitability becomes harder to maintain. The factors at play are complex and interwoven. Inventory costs must be balanced against cash flow, supplier terms, and seasonal demand. A shop in a town like Brownsburg would need to cultivate reliable relationships with regional distributors, maintain an assortment that captures both common components and obscure parts, and respond quickly to a customer’s pressing need. Each of these elements requires time, capital, and a certain degree of risk tolerance. When external pressures—such as a downturn in local demand, rising rents, or the strategic moves of larger competitors—coincide with internal constraints like limited working capital, the outcome can be swift and decisive. The dissolution date in 1989 is a silent testament to such pressures. It marks not just the end of a business entity but the moment when a particular interchange among customers, knowledge, and supply ceased to operate within that space.

Reading this narrative through a community lens also invites reflection on the social costs of such changes. Auto parts stores do more than sell components; they help neighborhoods maintain continuity of daily life. For a family needing a quick fix before a weekend trip, a local shop offers not only a part but also reassurance. For a new mechanic seeking to learn the trade, the shop can be a place to watch, ask questions, and grow skills. For residents who rely on their vehicle for essential trips—work, school, medical appointments—the reliability of transportation becomes a social good. When a local supplier exits, the community experiences a practical friction: parts may become harder to source, repair times lengthen, and the sense of a connected, responsive local economy diminishes. The broader economy may absorb the gap through larger retail channels or online supply chains, but the intimate neighborhood knowledge—the memory of who recommended a particular source for a stubborn brake issue, or which supplier reliably stocked a scarce gasket—often leaves with the shop’s closure.

Within the context of this chapter in the larger article on a&f auto parts, the case of A&F serves as a lens to examine how small enterprises contribute to a regional auto parts ecosystem. A&F’s existence—though limited in time—highlights the importance of place-based businesses in sustaining mobility infrastructure. It also underscores the vulnerability of small operators in an era when market concentration and supply chain rationalization can push independent shops toward obsolescence unless they find niche strengths. The recorded data prompts us to consider how similar entities, operating in other towns and counties, might have shaped their communities in quieter, less celebrated ways. Perhaps some supplied specialized components for local repair shops, enabling technicians to complete work more efficiently; perhaps others provided a network of informal referrals that helped residents navigate the confusing landscape of vehicle maintenance.

The social memory of A&F Auto Parts, even in the absence of a detailed community impact narrative, invites contemporary observers to think about how current auto parts ecosystems function in small towns. Today’s landscape features a mix of digital marketplaces, regional distributors, and local service providers who collectively keep cars on the road. In many cases, online platforms have supplanted some of the role once filled by neighborhood shops, yet the ethos of accessibility and responsiveness persists in different forms. The story of A&F reminds us that accessibility to parts and knowledge is as critical as the availability of products. It also suggests that the strength of a regional auto parts network lies not only in the breadth of its catalog but in the depth of its local relationships, the trust built through repeated, person-to-person interactions, and the willingness to offer practical guidance beyond the sale of a part.

As researchers and readers turn the page from archival records to living memory, the absence of explicit community outreach notes for A&F becomes an invitation rather than a limitation. It invites us to acknowledge that a shop’s true footprint often exists in the spaces between transactions—the conversations after a repair, the recurring customer who stops by to talk through a stubborn problem, the sense that a part is just a bit closer to home when sourced from a nearby storefront rather than a distant warehouse. The small-town auto parts shop thus embodies a microcosm of the modern economy: a balance between local fidelity and global supply capabilities, a tension between nimble service and the pressure to scale, and a continuous negotiation over what it means to keep a community moving.

In closing, the case of A&F Auto Parts, with its documented five-year life and its quiet dissolution, becomes more than a factual footnote. It is a narrative about the fragility and resilience of local ecosystems that sustain everyday life. It is a reminder that the health of a town’s roads is not guaranteed by engineers and asphalt alone but by the people who stock, source, and guide the parts that keep vehicles running. The memory of A&F—whether carried by local residents who recall the corner where the shop stood or by those who imagine a different retail landscape—invites continued exploration. It encourages current and future practitioners to recognize the value of place, to cultivate reciprocal relationships with repair professionals, and to consider how their own ventures might foster both business viability and communal trust. The chapter thus remains a meditation on the enduring interplay between commerce and community, a reminder that every storefront, even one that fades, leaves behind a trace in the road that matters to the people who rely on it.

For readers seeking a tangible thread that connects past and present, the broader arc of the auto parts economy offers one. The way communities adapt to shifting supply networks, the way small shops reframe their offerings to stay relevant, and the way knowledge travels across time all contribute to a richer understanding of how mobility is sustained. As roads continue to carry people to work, school, and opportunity, the memory of a modest Main Street shop persists in the stories, practices, and expectations that guide today’s buyers, technicians, and entrepreneurs. And while the specific chronology of A&F Auto Parts may be etched only in official records, its underlying lesson travels far: local enterprises, in their steadiness and their occasional fragility, are a living thread in the fabric of the community they serve. To honor that thread is to recognize that the health of the local auto parts ecosystem is not solely about what is sold, but about how trust, knowledge, and accessibility are maintained across generations of drivers and do-it-yourself enthusiasts. The continuity of movement, after all, depends as much on human relationships as on steel and rubber.

Internal link: For a sense of how online parts ecosystems now link buyers with needed components, see Mitsubishiauto parts resource pages and the surrounding community guidance at mitsubishiautopartsshop.com.

Rethinking the Local Auto Parts Trade: Circularity, Frugal Innovation, and Customer Trust in a Small-Scale Market

A small auto parts shop in Brownsburg, Indiana, once carried the quiet weight of a neighborhood enterprise. A&F Auto Parts Inc. registered in April 1984, operated for roughly five years under the watchful eye of local commerce and the legal framework that binds a for-profit corporation. Its footprint—1044 E Main St, Brownsburg—was more than an address; it was a node in a local economy built on trust, timing, and practical knowledge that every vehicle on the road carries a ledger of part histories. The dissolution on October 30, 1989, marks not just an end date but a data point in a broader conversation about why some small auto parts ventures endure while others disappear. The available corporate record is sparse in narrative detail, yet it provides a window into the lifecycle of a class of business that, in many ways, remains the backbone of automotive maintenance in smaller markets: the local supplier who must navigate supply cycles, price volatility, and the shifting tides of consumer demand with limited capital and a finite radius of operation. The story of A&F is not simply a tale of missteps but a pattern that recurs in the auto parts sector: the struggle to sustain a business model that is resource-intensive and precariously attuned to external shocks.\n\nViewed through this lens, the A&F case becomes a fertile ground for extracting lessons about sustainability in a sector that is inherently circular by necessity. A broader set of research results, including qualitative explorations of used automotive parts businesses in other regions, suggests that long-run viability hinges on anchoring operations in what economists and practitioners now call a circular economy. In such a model, a small shop survives not by selling new parts alone but by revalorizing used parts, refurbishing where feasible, and creating a loop that returns components into service rather than consigning them to waste. This reframing shifts the narrative from minimal compliance with environmental norms to a strategic approach that treats sustainability as a core driver of competitiveness. In practical terms, it means rethinking the value chain around the parts that come through a small shop’s door: sourcing, refurbishment, inventory management, and the promises made to customers about reliability and traceability.\n\nFrugal innovation emerges as another recurring theme in the sustainability literature that helps explain how small operators punch above their weight. The African context of used parts, cited in related studies, highlights the virtue of delivering practical, high-impact solutions with constrained resources. For a Brownsburg shop, frugality translates into lean procurement practices, selective refurbishment where cost-effective, and a business tempo that prioritizes turnover and cash flow. It does not demand grand capital investments to outpace larger players; it demands a sharper sense of what a local mechanic or DIY enthusiast actually needs, and the willingness to assemble a solution from adaptable, lower-cost components. The A&F case invites us to consider how such frugality, when coupled with a transparent and reliable sourcing story, can help a small operator cultivate a loyal customer base in a market that values quick availability as much as price.\n\nSustainability, as a driver of market value, takes on new meaning in the auto parts space when viewed from a consumer and lender perspective. In larger corporate studies, decarbonization and circular business models correlate with stronger market capitalization and broader stakeholder trust. While a neighborhood shop cannot influence market capitalization in the same way a multinational can, the logic translates into a palpable currency: trust. A shop that communicates clearly about where its parts come from, how they are tested or inspected, and how customers can verify compatibility and condition reduces perceived risk. In the Brownsburg context, where a customer might be returning to service a family vehicle or a fleet needing reliable uptime, trust becomes a differentiator that can offset price sensitivity. The challenge then becomes translating sustainability values into everyday practices: honest labeling, straightforward warranty statements, and accessibility of information about part provenance—without turning the process into a ritual of jargon that alienates the average customer.\n\nCentral to this transformation is the customer-centric mindset emphasized in contemporary insights about the auto parts ecosystem. The Accenture-inspired emphasis on understanding the end user—mechanics who need dependable components, do-it-yourself enthusiasts seeking value, and fleet operators demanding consistent performance—maps cleanly onto what a small shop like A&F would have needed to prioritize. If we imagine the Brownsburg shop evolving with a customer-first ethic, the path would involve more than just stock on shelves. It would require a service design that makes it easy to identify compatible parts, access reliable information about part condition, and obtain straightforward guidance on installation or fitment. When a customer trusts that a sourced used part is compatible and tested for safety, the door swings in both directions: repeat business from the local community and a stronger reputation in a market where word-of-mouth remains a powerful amplifier.\n\nTechnology, often the great enabler for scaling in modern retail, also casts a hopeful light on the fate of small auto parts shops. The tale of a modern direct-to-consumer auto parts platform demonstrates how digital tools can expand reach, improve inventory visibility, and elevate the credibility of second-hand goods through digital footprints, transparent sourcing, and customer reviews. For a small Indiana operation, digital technologies do not require a complete transformation of the business model; they offer a means to enhance stock control, streamline the process of matching part numbers to vehicle specifications, and communicate with customers in real time. The challenge remains to balance investment in technology with the realities of a smaller cash flow and a shorter planning horizon. Yet the potential upside is clear: better inventory discipline reduces waste, faster turnover improves liquidity, and trust-building features—like documented part histories and clear return options—enhance the perceived value of used components.\n\nThe A&F narrative, though quiet and concise in the official records, resonates with broader patterns observed in related analyses. The qualitative study of Africa’s used automotive parts trade underlines a common truth: small operators thrive when they become integral nodes in a circular network. They do so not by standing apart from waste and scarcity but by transforming those constraints into opportunities—through careful sourcing, value-added refurbishment, and direct engagement with customers who are seeking affordable, reliable repairs. The sustainability dividend is not merely environmental; it is economic and social. A shop that operates with a clear commitment to responsible reuse, transparent sourcing, and supportive customer service can unlock a resilient local ecosystem. In regions where supply chains are volatile and competition from larger players is intense, such a strategy can convert scarcity into a competitive advantage by building trust, reducing waste, and fostering community loyalty.\n\nBut the Brownsburg case did not unfold with a tidy payoff. The dissolution in 1989 serves as a sober reminder that sustainability concepts must be aligned with operational discipline, capital access, and adaptive response to changing market conditions. It invites a cautious optimism: the very factors that undermine short-lived ventures—fragmented supplier networks, narrow margins, and the assault of larger brands—can be mitigated when a shop embeds circularity into its core, uses frugal innovation to stretch resources, and maintains a relentless focus on the customer experience. The lesson extends beyond a single entity; it sketches a blueprint for similar ventures navigating the same terrain. If small auto parts shops are to endure, they must view themselves as within a larger loop rather than as isolated sellers of components. They must pursue refurbishing, revalorization, and transparent communication as integral business activities, not peripheral add-ons. In doing so, they position themselves to weather supply disruptions, price shocks, and the evolving expectations of customers who increasingly value sustainable choices as much as price.\n\nThese reflections do not diminish the value of scale or the role of large distributors. Rather, they illuminate a shared challenge: how to fuse the pragmatics of a five-year local enterprise with the strategic resonance of a circular, customer-centered, technologically enabled operation. The evidence from diverse contexts suggests a convergent path. Whether a small Indiana shop or a distant market studying used parts, the model that endures treats sustainability as a core capability, not a philanthropic afterthought. It embraces frugal means as a source of competitive advantage, not a euphemism for reduced quality. It makes customer trust the central metric of success, measured through reliable part histories, accessible information, and responsive service. And it harnesses technology not as a luxury but as a practical instrument to tighten the loop between supply and demand, so that parts move efficiently from sourcing to service, from storage to installation, and back into service life where possible.\n\nAs readers consider the lifecycle stories embedded in these chapters, the A&F Auto Parts case stands as a hinge point for thinking about sustainability in local markets. It is a reminder that business survival in the auto parts sector is not solely about inventory or price. It is about building a credible, resilient, circular system around the parts that keep vehicles on the road. In Brownsburg and similar towns, the enduring shops will be those that can narrate the provenance of their stock, demonstrate the reliability of their refurbishments, and communicate honestly with customers about what a used part can and cannot do. They will be the shops that engineer a culture of trust and a practice of continuous improvement, where lessons from dissolution become design principles for enduring practice. The chapter that follows our historical vignette must then be less about cataloging mistakes and more about translating these insights into an actionable path forward for small auto parts enterprises seeking sustainability, relevance, and enduring value in an evolving marketplace. The thread from A&F to the broader circle of practitioners is not merely academic; it is a practical invitation to reimagine a neighborhood business as a responsible, responsive, and resilient component of the local economy.\n\nFor readers seeking a broader perspective on how used parts ecosystems operate in other contexts, a comprehensive qualitative exploration offers valuable context. It highlights the commonalities across markets and underscores the universality of circular thinking as a lever for sustainability and resilience in the auto parts trade. See the broader study for a comparative lens on how similar shops navigate scarcity, supply chain uncertainty, and customer expectations in diverse environments: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/398765430AqualitativeexplorationofAfricanusedautomotiveparts_business. This external resource anchors the chapter in a cross-cultural understanding of reuse, value creation, and the social dimensions of automotive repair ecosystems, reinforcing the idea that the core tensions—and the core opportunities—are shared across geographies and market structures.

Final thoughts

The narrative of A&F Auto Parts invites reflection on the dynamics of small businesses in the auto industry. Despite its short-lived existence, A&F’s story sheds light on essential management principles and market challenges critical for today’s entrepreneurs. By examining their economic contributions, technological evolution, community role, and the lessons learned from its dissolution, current business owners can draw invaluable insights that pave the way for sustainable practices in an ever-evolving market. The legacy of A&F Auto Parts reminds us that every business journey, regardless of its outcome, offers lessons for the future.